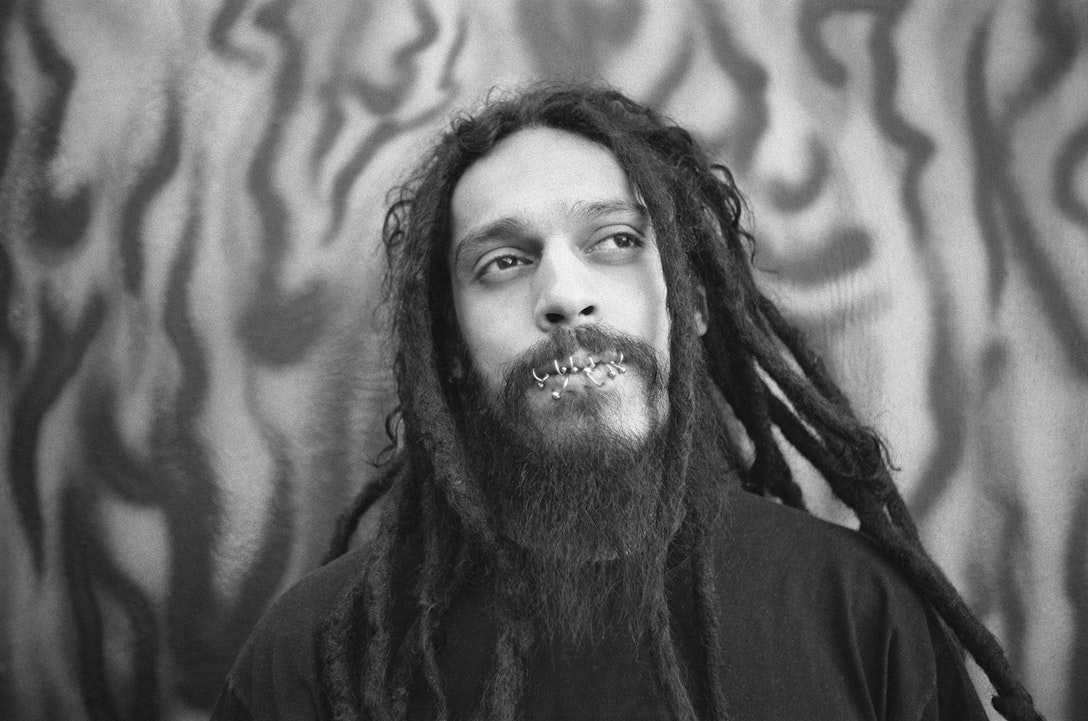

Davi da Silva

São Paulo, Brazil

EXCLUSION IN SPIRITUAL COMMUNITIES

I’ve been married for six years now; [my wife] plays together with me. We have a band, a Christian band [Death Snake], and we play death metal.

My father is an evangelical pastor. I understand that my calling is to tell of God, to talk about God, for a specific kind of people—for the underground people.

This all started because I was in my father’s church, a traditional church. One of my brothers left the church and began to get involved in this kind of lifestyle, and this kind of music. I started by talking to different churches, different pastors. I didn’t have long hair. I didn’t have piercings. But I went to these other pastors and said, ‘Hey, I have a brother. He’s in the underground movement. If I bring him here will you accept him nicely?’

And then they would answer me, ‘Of course! Bring your brother. We will...we will accept him with no problems.’ But they looked at me and I had a very ordinary look. So I understood that the problem wasn’t with my brother; that’s when I started to understand God. I would take my brother to those churches and ask him, ‘So did you like the church? Did you like the pastor?’ But then people would give weird looks.

And then I understood that although my brother and I were the same inside, on the outside my brother had long hair, he dressed in black, and he wasn’t accepted there. So I understood at that moment that my calling was to go for these people.

Once, after we finished preaching, one person came to me and asked me to go with him across the street. This guy said to me: ‘I came to your concert last night. I had a lot of cocaine in my head and I decided to kill myself. But something changed my life during your concert. Your wife, she went to the mic and said, “There is somebody here with a spirit of death. And I want to say that God took us from Brazil to come here to speak to you to say that there is more for your life than killing yourself and...” and after your wife finished saying that, I ran like crazy. I went to my house and people were saying, “What’s going on?” I locked myself up in my room. And I had a crazy night questioning: Is there a God? What's going on? How does this person know about what's going on with me?’

And then this person [said], ‘Well, today I’m here because I have heard of this God, and I want to have an experience with this God ’cause I understand that he cares about me.’ And then this guy threw a bunch of cocaine on the floor. I never saw so much cocaine in my life. He said, ‘I don’t want this anymore. I want God. I want the God that you're preaching.’

God is not looking at their appearances. God is not looking at your sins, your mistakes; he just looks at your potentials. And that’s what I want people to see in me. Don’t want them to look at my look, I want them to look at themselves and think, ‘If God likes this guy...if God loves this citizen, God loves me, too.’”

Daniel’s Reflection

I met Davi da Silva at the Zadoque Church in São Paulo, Brazil in the very first week that Portraits in Faith became an international project. The Zadoque Church caters to “underground” Christians who are part of the tattooed, pierced, leather-wearing, or goth-dressed counterculture. Davi defied all my preconceptions of someone with multiple pierced rings across his upper and lower lips. He turned out to be a beautiful soul filled with devotion to the cause of loving all of humanity—a great lesson for me in prejudging others.

I was touched by Davi’s story that he really only joined the underground world when he tried to find a church home for his brother who had turned to counterculture and could find no church that would accept him. So as I reflect on this beautiful human being, Davi da Silva, I am also reflecting on why we push people away and reject those whose appearances are different. I questioned a professional colleague from my marketing and innovation work who has a strong background in evolutionary psychology and behavioral science. He shared this perspective with me by email:

“Humans have a fairly well documented ingroup- outgroup bias. From an evolutionary perspective, your own tribe was generally safer than strangers, so we have implicit bias to favor our inner circle. Humans are cognitively lazy, so will default to simple differentiators to define that inner circle, and more importantly, to identify strangers/outsiders. Probably the easiest is simple recognition, and trusting/liking people we know. But in the absence of that, in modern society where we need to deal with much larger numbers of people than we evolved to manage, it's fair to speculate that skin color or other visual markers like piercings are an obvious cognitively and perceptually simple default differentiator. I think there's already a partial answer in there, as we don't tend to see discrimination based on hair color. I suspect that is because we cannot effectively group people by hair color, because it doesn't correlate with any effective societal boundary. There may have been at one time, but now that we don't have villages of redheads or blondes—we are all so mixed up that it's not useful. Without a corresponding pattern, the perceptual cue is (unconsciously) disregarded. I suspect the reason skin color is potentially still an in group/out group differentiator is because we are still societally grouped by race, at least to some degree, and especially in the U.S. So we have a correlation between a simple visual marker and a societal demographic effect. If that is right, then the obvious answer is true integration, in where we live, where we play, where we work, and in entertainment. And start with schools, because habits and biases are more plastic early in development.”

So to explore this I will start with my own Jewish tradition and the commandment to “Love thy neighbor as thyself.” What does it mean to love my neighbor as myself? Rabbi Rachel Kaplan Marks, of Congregation Shalom in Fox Point, offered this beautiful commentary from the Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle newspaper:

“In her teachings, Nehama Leibowitz draws attention to the writing of R. N. H. Weisel who offers, ‘Love thy neighbor who is kamocha as thyself—like you, created in the image of God, a human being like yourself.’ In other words, perhaps kamocha refers to the notion that each and every human being is created in God’s likeness; therefore, we all share a godly likeness with one another, and thus if we love God, then we must love each other."

“Our sage, Rashi, quotes Rabbi Akiva’s teaching that the commandment, ‘love your fellow as yourself’ is a klal gadol—a central principle of Torah. Perhaps, however, this principle is central not only because it creates a culture of kindness and decency among people, but rather it is a central principle because we acknowledge our likeness to God by emulating God and showing love to one another.”

Turning to the Christian tradition, I am struck by Jesus’s parable of the Good Samaritan. Most of us, across religions, know of this story or at least the metaphor of a good samaritan. But the story itself is powerful and changes who we think of as our neighbor. I love this interpretation by my former Procter & Gamble colleague, Barron Witherspoon, Sr., who wrote a powerful book, The Fallacy of Affinity: A Case for Cross-Cultural Worship, about the need for mixed-race congregations and worship:

“This parable is given by Jesus in the context of an expert in Jewish law asking ‘Who is my neighbor?’ You see, Jesus was teaching this lawyer to re-think his notion of the neighborhood, even his notion of brotherhood. Jesus was teaching him that ethnic and racial affinity is not the determinant of brotherly love. He was teaching there is honor in extending oneself across traditionally taboo barriers of race and class and investing in the physical (and spiritual) development of others. We see in this example, Jesus fully intended for the outcast to be brought into the family of God.”

And, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. actually expounded on the lesson of the parable of the good Samaritan in his 1967 sermon: “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence,” delivered at Riverside Church in New York City.

In this sermon, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. reminds us that the real goal is not just to follow the role model of the Good Samaritan but even more we need to transform our world where people become beggars and get beaten up.

So, returning to my wise and esteemed colleague, Barron Witherspoon, Sr., he raises important questions about why we prefer to worship with people who look like ourselves when the message of Jesus and other prophets was clearly opposite to this:

“I wonder why we lay aside our ability to adapt when we enter the church. We somehow forget how to change ourselves and we lose interest in anything which requires us to adapt a new practice. If you want to see inflexibility and a lack of adaptability suggest something be changed in your church. People want to enjoy routine in church. We want to sit in the same place, sing the same songs, listen to the same messages, fellowship with the same people, and enter and leave the worship service at precisely the same time each week. Change any of these particulars and you will witness the most vigorous objection. To what are we objecting? We are objecting to change, and in doing so, we invite extinction upon ourselves. We are setting aside all our God-given adaptability in favor of extra-Biblical preferences. You see, we often do not get our preferences for where to sit, what to sing, and what instruments to play from the Bible. We get these preferences from generations of repetition. Like the animal whose current food source has become his only food, our current worship styles have become our only way to worship. Any other food is not really food, and any other worship style is not really worship. I don’t know about you, but I would rather be part of building up the church than facilitating its demise.”

So if the lesson is to embrace everyone as my neighbor, then how do we understand the music of a counterculture like death metal actually being sacred music? I found a scholar whose doctoral dissertation was about more deeply understanding Christian heavy metal music. Eric Strother, Ph.D. explains this cultural mash-up as follows:

“Christian metal bands show images of death, destruction, and the demonic, and they do so in part because that is what is expected of metal bands in certain subgenres. It is fallacious, however, to assume they arrive at these images because they are fascinated with evil and chaos. Instead, they hold a perspective that those images reflect the state of ‘the world’ without the light of Christ in it. As one member of the Christian thrash band Temple of Blood stated, ‘[M]etal is about dark topics. Christian metal tends to focus on dark Biblical topics.’

...

“Many of the ideas on both sides of the Christian metal debate are based in the view that some forms of art are inextricably associated with a particular moral position. It is a perspective that dates at least to the writings of Plato and Aristotle, who both believed particular musical modes were inherently connected to particular states of mind. In the modern era, this view creates a peculiar irony surrounding the Christian metal scene: despite the contempt many within the Christian Church and general market metal scene feel toward each other, many share the same opinion that Christianity and metal music are not compatible because metal is inherently ‘evil.’ What both sides often do not accept is the view that music, as a system for organizing sound, has no absolute morality. Leonard Cohen’s ‘secret chord’ that is pleasing to God is a myth in the same way as Satan’s preference for the tritone is. Music has the capacity for inspiring an emotional response from the listener, but the nature of that response is far from universal, it is culturally-based and is within the control of the listener.”

So if I understand correctly the lessons of meeting Davi: Everyone is my neighbor—no exceptions— even those my culture tells me to hate and fear. I love and care for my neighbor because I want to be in a relationship with my Higher Power and every human (and all of creation) because all are an expression of the Divine. It is important that houses of worship and I must work to make where we worship more diverse than it is today. I need to not judge so quickly new and unusual-to-me forms of self-expression and ways of reaching out for a God-connection.

Thank you Davi da Silva for your big, pierced smile and loving heart!

REFERENCES & PERMISSIONS

Marks, Rabbi Rachel Kaplan. “Opinion: Choosing Love over Hate in Torah.”

The Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle. May 3, 2016.

www.jewishchronicle.org/2016/05/03/opinion-choosing-love-over-hate-in-torah/

Permission to quote text from The Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle was given to the author

by Rabbi Rachel Kaplan Marks on August 12, 2021.

American Rhetoric Online Speech Bank. Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. “Beyond Vietnam -

A Time to Break Silence.” Delivered April 4, 1967 at Riverside Church, New York City.

www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkatimetobreaksilence.htm

Witherspoon, Barron, Sr., Rev. 2010. The Fallacy of Affinity: A Case for Cross-Cultural Worship.

Dog Ear Publishing, LLC.

Permission to quote text from this book was given to the author by Barron Witherspoon, Sr.

on August 5, 2020.

Strother, Eric S. “Unlocking the Paradox of Christian Metal Music.” (2013).

www.uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1010&context=music_etds

This doctoral dissertation is available for free and open access through UKnowledge,

www.uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/9

Explore the portraits by theme

- happiness

- grief

- faith

- addiction

- sexuality

- sobriety

- transgender

- alcoholism

- suicide

- homelessness

- death

- aggression

- cancer

- health

- discipline

- abortion

- homosexuality

- recovery

- connection

- enlightenment

- indigenous

- depression

- meditation

- therapy

- anger

- forgiveness

- luminaries

- interfaith

- worship

- salvation

- healing