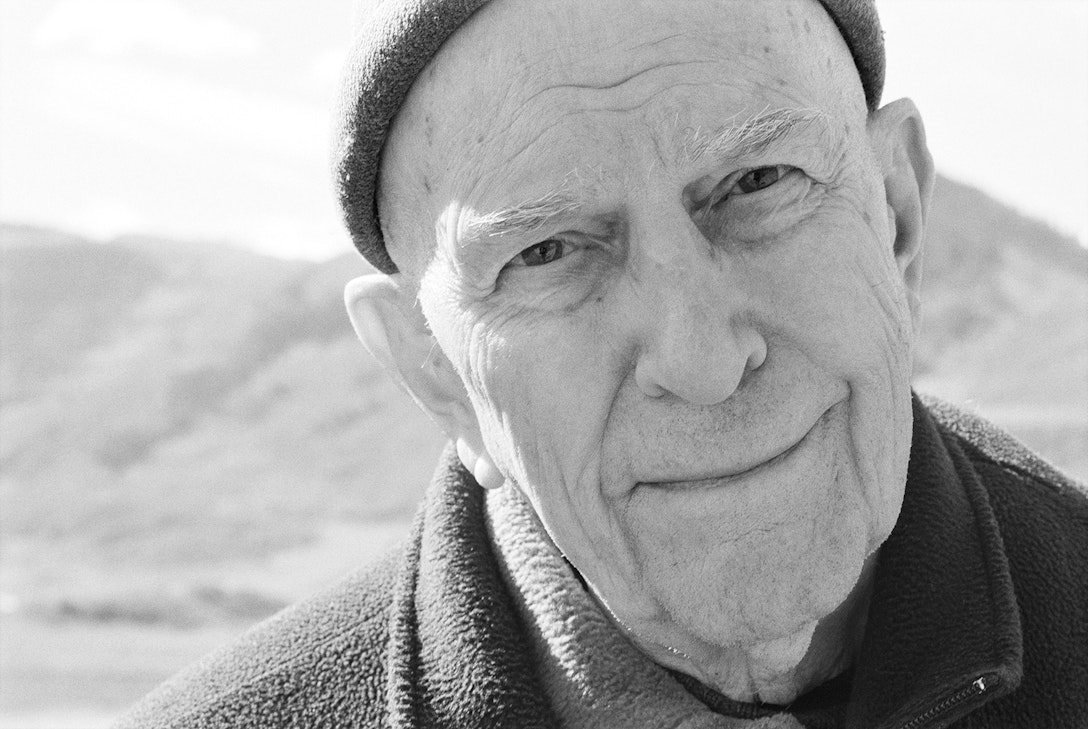

Father Thomas Keating, OCSO

Snowmass, Colorado, USA

Father Thomas Keating’s Journey

My first year at Yale I experienced a significant crisis of faith. And I thought of whether I would continue to practice the Roman Catholic practices of the mass and the other important rituals. So I read this book by Tolstoy because I was in a class of contemporary philosophers and he was rated as one. He wrote a book about the Sermon on the Mount to attack the bourgeois observants of Christianity. Perhaps you're aware that he had a great estate in the old Tsarist regime. After his conversion to Christianity, he gave up a lot of his wealth and he started working with the serfs on the estates. And he also was a friend of Gandhi. He was noted for his non-violent sympathies towards the end of his life.

What about being poor if you want to be a good Christian? That concept impressed me since I came from a fairly well-to-do household. My father finally achieved that. The dream of his life was a significantly large house in Long Island, looking east over Oyster Bay. The Yankee Clipper used to fly over our house when that started going years ago. I never actually heard my father argue a case except once. So his life as a lawyer was something that took place outside of the realm of our experience. He was very good,I gather, because he argued many times before the Supreme Court and was involved in representing the underwriters in all the great shipwrecks, like the Morro Castle case.

So his dream was that I would take his place, of course, and that was the last thing I wanted to do. And it especially became evident as I began to commit myself completely to studying history. And I studied it so well that I almost flunked out of Yale because though I had graduated fairly high in the class, I lost all interest. Nothing at Yale interested me at all except the Catholic Church that was there and the opportunities I had to study. I really didn't have anybody to direct me in those days. Not many people were familiar with the tradition. I couldn't find anything out from other people about it. So I committed myself more and more and began to pray a lot, or meditate a lot. And I read the Christian mystics. For two years I gave myself a course in the Christian mystical tradition, and that led me to want to find a way of life in which I could permanently pursue this with the maximum hope of good results.

In those days it was thought that the best place to pursue a life of serious prayer and meditation was in a cloister. So I looked around. The second thing that was considered was a hard life; very strict and separated from the world. I found the Trappists and I think I succeeded in finding that...it was pretty tough. I finally entered at the age of 20; I had to wait to be almost 21 because my parents were totally against it. It was a choice of values that were the direct opposite of those that my poor father had. And so he was really emotionally shaken up by my choice. In those days, I wasn't too concerned about what they felt 'cause I felt I had to follow what I felt was my vocation and if they didn't like it, that was their problem. So there was a certain amount of selfishness involved in my thinking. Later I began to sympathize more with what they went through. It was a hard enough decision for me with my own dependencies on people, and various things that make life pleasant. So I radically gave up everything I had and committed myself to that life.

Daniel’s Reflection

I met Father Thomas Keating at the monastery he called home twice in his life in Snowmass, Colorado. This meeting took place because of a suggestion by his friend and colleague, Reb Zalman Shachter-Shalomi, may both of their memories be for a great blessing. Thomas Keating was a larger than life figure in the world of meditation and was credited for bringing meditation back into the Christian tradition. He called this approach to meditation “Centering Prayer.” St. Benedict’s Monastery in Snowmass, where Keating lived, became a haven for meditation retreats, especially Eleventh Step meditation retreats for the 12 Step world. I feel so fortunate that I got to meet this soulful giant of a man, especially having met him in his later years when he had so much to reflect upon from his journey. He challenged me to think of Portraits in Faith in a new way.

Thomas Keating grew up the son of a very financially successful lawyer but he had no interest in following in his father’s footsteps. While at Yale, he became enamored with the Christian mystics and pursued study of Catholicism rather than focusing on his studies. Upon graduation, he pursued that religious vocation with the most stringent, demanding order he could find—the Trappists. He visited with monks in the Far East and brough lessons back to incorporate into Christian contemplative practices. Keating embraced the spirit of Vatican II and became a fierce leader of interfaith engagement as evidenced by his close friendship with Reb Zalman. He spent most of his adult life between two locations—St. Joseph's Monastery in Spencer, Massachusetts where he was an abbot for many years and St. Stephen’ss in Snowmass that he helped found and start. It was where he spent his years after retiring as abbot. Father Keating died at St. Joseph’s on October 25, 2018. I interviewed him in 2003.

I took away three big lessons from the brief time I spent with Father Thomas Keating:

-

We must reject our parents’ plans for us even if we later reclaim them as our own. I so admire the sense of internal authority and calling that Keating experienced that he turned down his parents’ wanting him to become a lawyer. In fact, he really rejected what most of his classmates were likely pursuing at the very elite Yale University. He even received a deferment from the draft to attend Seminary. I love this explanation by Pastor J.D. Greear who helps me reconcile the commandment to honor our mother and father with the necessity of forging our own path:

When we are young, our parents represent the authority of God to us. In a way, they stand in for God for a time. We first learn to obey and submit to God by obeying and submitting to our parents. Parents are only a temporary stand-in for God. They are like the training wheels for learning how to obey God. When you’re learning to ride a bike, training wheels are critical. But the training wheels were never the point. Riding the bike was. In our relationship to our parents, the goal isn’t mere obedience. It’s a healthy and honoring family relationship—and, more importantly, a trajectory toward God. As a child, you honor your parents by obeying them. When you are older, you honor them by being the man or woman that God designed you to be and by obeying God, even if that means sometimes you go against your parents’ wishes. By obeying God, you are honoring the institution of parenting. Which means that for some of you, the best way to honor your father and mother is to defy their wishes and do what God says.

-

Choosing the hardest path brings great rewards. I am inspired that Father Thomas Keating was energized to find the most stringent and difficult path in religious life, the Trappists. Father Thomas described to me the extensive fasting and prayer regimens that he endured but saw as critical to his spiritual ripening.

It made me reflect that the hardest path is often the path that brings the sweetest rewards—not the easiest path. This has certainly been true in my life. I chose two up-or-out companies where I spent the majority of my career (Price Waterhouse and Procter & Gamble). Neither was easy and often I was the one creating the difficulties! But I am grateful for the difficulty and challenge each environment provided in preparing me for what I am able to do professionally today. No quote communicates this more potently that President Kennedy’s famous speech about why we went to the moon:

William Bradford, speaking in 1630 of the founding of the Plymouth Bay Colony, said that all great and honorable actions are accompanied with great difficulties, and both must be enterprised and overcome with answerable courage. We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.

-

Even the spiritual journey is filled with ego traps that cause us to focus on the self. I was disturbed in my interview with Father Keating when he seemed to skirt some of my questions with brief and simple answers. They were important questions to me, such as, “What is your earliest memory of faith?” and “When was the first time you felt like you had to rely upon God?” He said that the answers to these questions did not really matter anymore and that there were more important things to focus upon.

I must have been struck by a lightning bolt of clarity when I asked him: “Are you suggesting to me that even the remembering of one’s own spiritual experiences is too much of a focus on the self?”

He said “Yes!”

Wow, I felt simultaneously deflated and energized to have come upon that great insight; that even the spiritual journey and the recounting of it are filled with numerous opportunities to be ego-focused.I am so grateful to Reb Zalman Shachter-Shalomi for directing me to his friend and fellow traveler, Father Thomas Keating. I am grateful for the way in which Father Keating confronted my beliefs about authority, the harder path, and about the pitfalls of the spiritual journey.

Permissions and References

Permission to quote Pastor JD Greear provided by his Summit Life Team of JD Greear Ministries on 7/15/24. J.D. Greear is the pastor of The Summit Church in Raleigh-Durham, NC.;

President John F. Kennedy, “Address At Rice University” on the nation’s space effort, Houston, TX, September 12, 1962.

Explore the portraits by theme

- happiness

- grief

- addiction

- sexuality

- sobriety

- transgender

- alcoholism

- suicide

- homelessness

- death

- aggression

- cancer

- health

- discipline

- abortion

- homosexuality

- recovery

- connection

- enlightenment

- indigenous

- depression

- meditation

- therapy

- anger

- forgiveness

- Doubt

- interfaith

- worship

- salvation

- healing

- luminaries