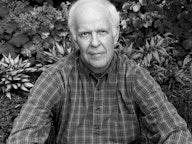

Pastor Gottfried Brezger

Berlin, Germany

FAITH AND MONEY

Marx’s criticism of existing conditions and the fetish of money...and in the end, people over-valuing money, is something I learned from Marx. Theology, as well as Marx, says, ‘Faith and money have been exchanged. Money is only a means to an end and not the end itself.’ Why are we devoted to money and not the person who has given us the things that money can buy?

The thing that I learned as a child is a primal sense of trust. That the world behind the world around us is a good world because this is the world that God has given us. God is, for me, benevolent. God is the one without whom I do not want to live.

Daniel’s Reflection

I never had a desire to visit Berlin. The place was too wrapped up in my understanding of the Holocaust. I grew up in a family that did not buy German goods. I even remember when I had to give back a Hohner harmonica I once got as a birthday present. These cultural norms run deep and can imprint deeply as well, especially in children. While I went to Frankfurt fairly often for business, Berlin carried a much heavier weight. But these are also cultural biases and norms that needed to be confronted with healing in order to move forward. I finally went to visit the city of the Brandenburg Gate, the Reichstag, the Berlin Wall, and conducted Portraits in Faith interviews. It was a perfect way for me to experience this great city, and I found it to be uplifting and generative.

Gottfried Brezger was the pastor of a German Lutheran church. While his father was a pastor as well, he walked away from religion as a young adult in reaction to his disappointment that his church did not resist enough during World War II (the Nazi/ Holocaust era). He even joked that he and his wife were both reading Karl Marx on their honeymoon! It was eventually through his deep concern for the well-being of others and his understanding that some of the most resistant leaders were religious, that Gottfried returned to the church and became a pastor. Here is a man who has grieved and re-conceived his relationship with God.

One of the most interesting and important tasks of Gottfried’s life is his study and preserving the memory and teachings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a Lutheran pastor, theologian, and anti-Nazi dissident. Bonhoeffer was executed by the Nazis in 1945, just weeks before Germany surrendered, after Bonhoeffer’s participation in a plot to assassinate Hitler. Today, Pastor Brezger is the caretaker of the Bonhoeffer family home in Berlin which he set up as a place of learning and dialogue. I was fortunate to return to Berlin where I spent an afternoon in the center learning about Bonhoeffer’s legacy.

Because of Pastor Brezger, I have subsequently studied the words and life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. I am in complete awe of this amazing man who was a true martyr for his faith in the 20th century. His faith was rooted in a belief that we must live in reality, including the reality of evil such as Nazi Germany.

Bonhoeffer wrote: “I remember a conversation I had thirteen years ago in America with a young French pastor. We had simply asked ourselves what we really wanted to do with our lives. And he said, ‘I want to become a saint’ (and I think it’s possible that he did become one). This impressed me very much at that time. Nevertheless, I disagreed with him, saying something like: I want to learn to have faith. For a long time I did not understand the depth of this antithesis. I thought I myself could learn to have faith by trying to live something like a saintly life... Later on I discovered, and am still discovering to this day, that one only learns to have faith by living in the full this-worldliness of life. If one has completely renounced making something of oneself—whether it be a saint or a converted sinner or a church leader (a so-called priestly figure!), a just or an unjust person, a sick or a healthy person—then one throws oneself completely into the arms of God, and this is what I call this-worldliness: living fully in the midst of life’s tasks, questions, successes and failures, experiences, and perplexities—then one takes seriously no longer one’s own sufferings but rather the suffering of God in the world. Then one stays awake with Christ in Gethsemane. And I think this is faith.”

While Dietrich Bonhoeffer fled to America during World War II, he concluded that he had to return to Nazi Germany to be an active part of opposing and even trying assassinate Hitler. Bonhoeffer wrote to theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, Ph.D. from New York at the end of June 1939: “I have come to the conclusion that I have made a mistake in coming to America. I must live through this difficult period of our national history with the Christian people of Germany. I will have no right to participate in the reconstruction of Christian life in Germany after the war if I do not share the trials of this time with my people.” Bonhoeffer paid with his life for this decision.

Ultimately, Bonhoeffer best defined what an active faith means to me when he said how we must wrestle the steering wheel from the maniac in our midst. His fellow prisoner Gaetano Latmiral reported a statement from Bonhoeffer in the Tegel prison: “If a maniac drives his car over the sidewalk on Kurfürstendamm, I as a pastor cannot only bury the dead and comfort the relatives; I have to jump over and pull the driver off the wheel when I’m standing there.”

I am so deeply moved by what pastor Gottfried Brezger taught me about faith by sharing with me his own life journey from atheist socialism to the active faith of his Lutheran Christianity and the legacy and martyrdom of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. They don’t teach you that in Hebrew school but they should!

Thank you Gottfried Brezger for your beautiful faith journey and your own service to humanity.

Explore the portraits by theme

- happiness

- grief

- faith

- addiction

- sexuality

- sobriety

- transgender

- alcoholism

- suicide

- homelessness

- death

- aggression

- cancer

- health

- discipline

- abortion

- homosexuality

- recovery

- connection

- enlightenment

- indigenous

- depression

- meditation

- therapy

- anger

- forgiveness

- luminaries

- interfaith

- worship

- salvation

- healing