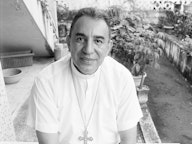

Lenny Baptiste

Penticton, British Columbia, Canada

THE DECISION TO NOT FORGIVE

I had so much hatred in me when I was young and being abused in residential school. I actually faced that person when things were happening to me and I would just look at them blank. I never had any emotion. I just looked at them and I thought in my mind ‘I’m going to get you one day. I’m going to find you and I’m going to get you and probably kill you.’ As I was growing up I’d go from town to town. I’ve been to Mexico and all over the place. Every town I would go to I would look in the phone book for their names.

Around 2003, I went to a healing gathering in a residential school. It was one of the first ones they were starting to have. I looked in the phone book— and there was his name. My buddy was with me, and the same thing happened to him with that same person. We were looking at this name and we were just wild. I said, ‘We gotta phone this guy.’ So I phoned and a woman answered. I said, ‘Is this so and so? He used to work here.’

And she says, ‘Ya, that’s him.’

I said, ‘I want to see this guy.’

She said, ‘Who are you?’

I said my name and there was a silence...a silence I can never forget. Then she said ‘Ya, he’s been waiting for you.’

I asked if it was alright for me to come over.

She said, ‘Ya, you’re welcome to come over.’

I thought this was strange because the first thing you’re gonna do is call the cops. I went over there, knocked on the door and this woman appeared. I thought I was at the wrong house because in the back living room there were graduation pictures of two Native kids, and this was a Native woman. I thought this couldn’t be right because this was a white guy. I asked if there was a mistake. She said, ‘No, this is him...this is his house.’

I said, ‘Oh no.’ My thought pattern changed because I was dealing with my people. There was a lot of anger.

We got there about 3 o’clock, and he was coming around 6 o’clock. In that time, she told me his story; what happened to him. She said he kept seeing my face and the look on my face and he said that drove him down. He ended up in a psych ward and knew that one day I would look for him and find him.

I was going to kill this guy and so everything had changed. The whole time I had to talk my buddy down because he was worse off than I was. I said, ‘Let’s see this guy’s story.’

So he got back and we saw he was a frail old man. He was shaking. He knew we were coming and he walked in and we looked at him and we sat down and we started to talk and he asked me to forgive him.

All this energy was in me...all this bad energy...and I said, ‘I can’t...I can’t undo that...I can’t forgive you.’ To me, forgiving is like letting go, forgetting, and it’s gone. But this was always going to be there so I couldn’t forgive him. I said, ‘Obviously you’ve worked through it and you’re OK now and now it’s all on me.’

His wife asked me if I could forgive him and I said, ‘I can’t, I can’t forgive.’ It says in the Bible that you forgive but it’s not like that when things happen in your life...you can’t do it. And I said, ‘Well let’s look for another way.’ We looked and looked and she finally came up with a ‘pardon.’ I said, ‘Explain to me what a pardon is.’ She explained to me what a pardon was and I said, ‘I can do that.’ So in my mind and my heart, I gave this guy a pardon. The minute I did it, I could speak without a stutter. It was amazing. It’s what they call a miracle. The stutter was gone. I heard that and it was gone. I could actually speak the way I am speaking now.

Daniel’s Reflection

When is it the right decision to not forgive someone for harming you? Many of us would answer: “When that person has not truly accepted the harm they committed or taken full responsibility to repair all damage done.”

In Judaism we have the concept of teshuva which literally means “to return.” It is a wonderful metaphor for the work necessary internally and externally when we have committed harm. So if a person has not done their teshuva, we might say we do not need to forgive them. Yet, as a Jew, I’ve always been fascinated by, and jealous of, how Christians are urged to forgive. I was amazed in 1981 when Pope John Paul II forgave his would-be assassin just one day after the shooting.

This whole discussion of forgiveness gets elevated to another level when it is a societal harm against one group of people by society at large. This is the case with Lenny Baptiste and the generations of First Nations (Indigenous) peoples who were forced into Catholic “residential schools” where they experienced physical, sexual, and emotional abuse.

In a powerful article in Psychology Today (Sept. 25, 2014), David Bedrick, J.D. advises psychologists to not always guide their patients to grant forgiveness, especially in situations involving harm to a societal group as a whole:

“...Advising forgiveness, or letting go, to groups of people who have suffered sustained injustice is often ignorant and highly suspect.

“Post after post and article after article preaches forgiveness while failing to address the injuries created by sustained social prejudice and marginalization. Instead of addressing these ills, forgiveness is discussed as if it were only an individual process—one person forgiving another. In a way, conventional thinking about forgiveness ignores some of the most profound injuries of our time, rendering this advice ignorant and even complicit with regard to the history of race, gender, and other issues of diversity:

“First, it ignores the great strides that have been made by women, African-Americans, homosexuals, the disabled, and other marginalized groups by people who took the seed of their vengeance and anger and turned it into social action. They didn’t only practice letting go. They harnessed their rage, vengeance, and anger to lift their arms and voices for the benefit of many—and the development of America’s democratic project.

“Second, it ignores the fact that powerful prejudices still exist making these injuries not just a thing of the past. Shall we forgive an abuser in the middle of their abusive act?

“Finally, this counsel often comes from people or groups who either have more social power, or a vested interest in not having to look in the mirror at their culpability or redressing the ills many have suffered.”

Lenny Baptiste was able to heal his own wounds with a combination of traditional Native practices with medicine men, and through a lifelong, dedicated practice of the martial arts. But when it came time that he was face-to-face with his abuser, he was unable and unwilling to forgive him, even seeing that this was now an elderly and broken man. I do not know the exact definition of “pardon” that was offered to Lenny but I assume it was a decision to not bring charges or pursue punishment. I understand that sometimes forgiveness itself cannot be given. We have to honor it when that is the decision of the abused and when withholding forgiveness will actually advance the ethical and moral standing of our society.

Permissions and References

-

Bedrick, David, J.D., “6 Reasons Not to Forgive, Not Yet.” Psychology Today. Sept. 25, 2014.

Permission to quote text from this blog post was given to the author by David Bedrick, J.D. on August 8, 2018.

Explore the portraits by theme

- happiness

- grief

- addiction

- sexuality

- sobriety

- transgender

- alcoholism

- suicide

- homelessness

- death

- aggression

- cancer

- health

- discipline

- abortion

- homosexuality

- recovery

- connection

- enlightenment

- indigenous

- depression

- meditation

- therapy

- anger

- forgiveness

- Doubt

- interfaith

- worship

- salvation

- healing

- luminaries