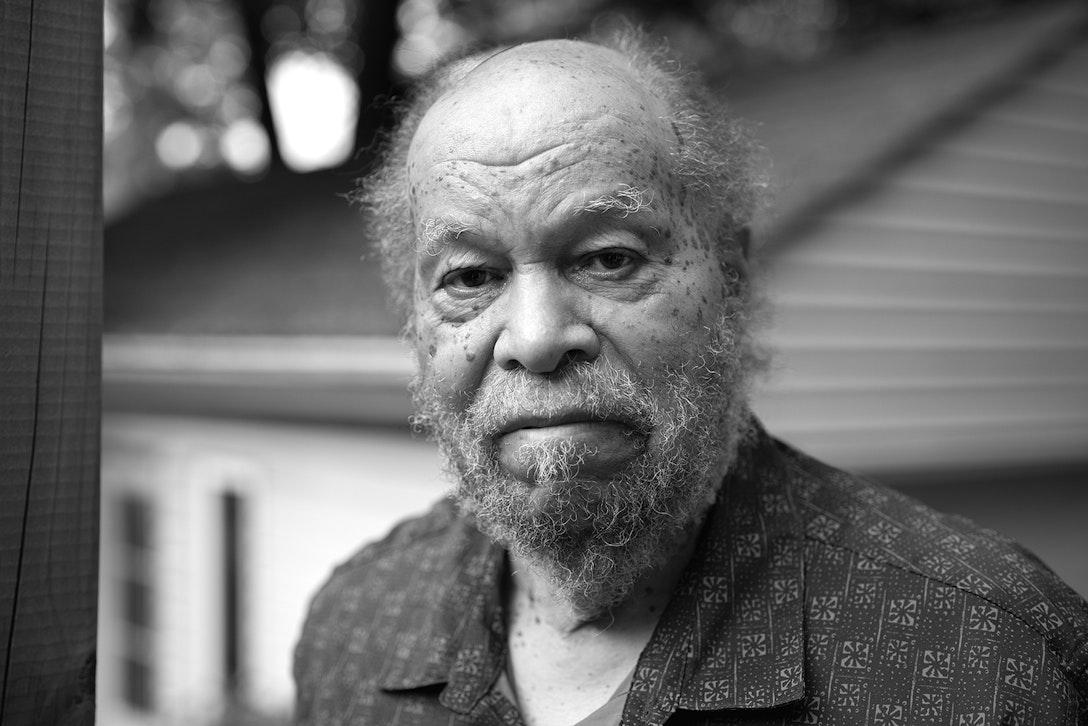

Lowdru Robinson

Portishead, England

Confronting Apartheid in Bermuda

This was on a Sunday night. And there were three or four of my friends. And this particular night, after the service—a religious experience where the message was that everyone is a child of God—we were passing by a restaurant and we decided to go in for a Coke. So we all went in. We sat down. We were all nicely dressed. They refused to serve us and made us leave. And here they were...because we were the wrong color. They literally told us: “We don’t serve ‘you know what’ in here.”

From that point on, I had a concept of God, but it didn’t mean anything to me because I couldn’t understand it: if there was a God, and I’m a person, and white people are persons, why are they treating me like this if we’re all going to end up going to heaven?

I used to go regularly to a barber shop and my barber would always talk to me in terms of human relations, of people being human. He said that it doesn’t matter if you're black or white; there will come a time when people will be treating each other equally.

I thought this guy was insane. Bermuda is a segregated place and he was talking like there was an opportunity to be equal.

So I said to him, “Where are you getting these strange ideas from?”

He said, “Well, I’ll give you a couple of books, and you can check for yourself.”

It turned out they were Baha’i books, and he was a Baha’i. When I read some of the writings in the Baha’i books, I suddenly got a totally different feeling, because I felt that I was human and I should accept somebody who’s white because they are also human and they should accept someone who is black. Instead of hating white people per se, I started feeling sorry for them because they didn’t know that we were both equal in terms of our humanity, and therefore, we should be treating each other better. After reading a number of the books that the barber gave me, I actually became a Baha’i and joined a group that was trying to promote better race relations.

The first thing that really struck me when I met the Baha’i members was that they were black and white people—I was shocked—who were treating each other equally. That was better than anything I’d ever even read—the actual way they treated each other. Some of the ones who were white were in families that wanted to disown them because of the kind of relationships they were having. They were having a difficult time, but they obviously accepted this concept and were prepared to work towards better relationships. So that was a real turnaround for me.

Explore the portraits by theme

- happiness

- grief

- addiction

- sexuality

- sobriety

- transgender

- alcoholism

- suicide

- homelessness

- death

- aggression

- cancer

- health

- discipline

- abortion

- homosexuality

- recovery

- connection

- enlightenment

- indigenous

- depression

- meditation

- therapy

- anger

- forgiveness

- Doubt

- interfaith

- worship

- salvation

- healing

- luminaries