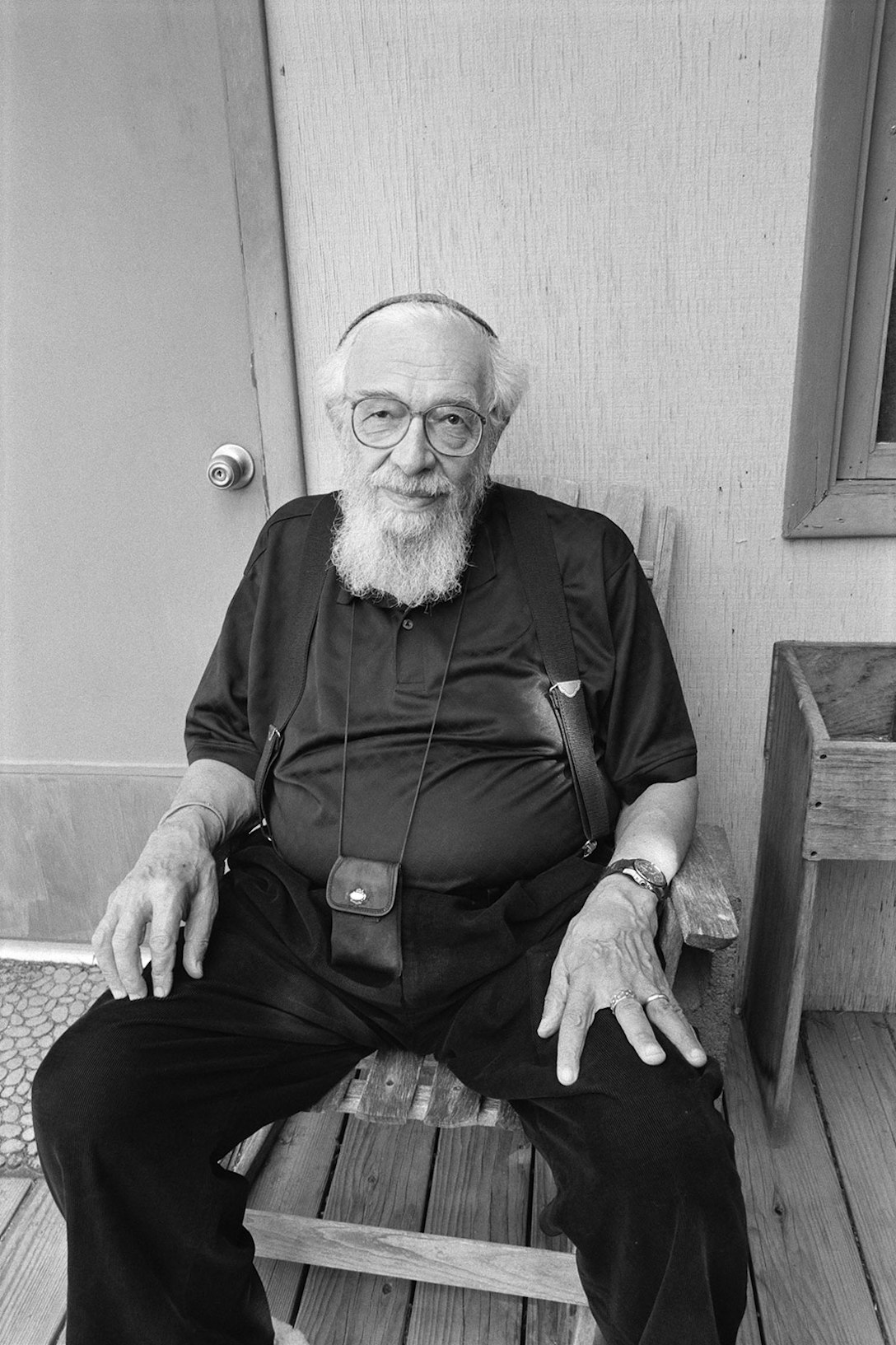

Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi

Boulder, Colorado, USA

SPIRITUAL LIFE EXPERIENCES

Earliest Memories of Faith: As a child, I would walk by a little side chapel in a big church and the ladies would be lighting candles and standing like my mama did on Shabbos [Sabbath]. And papa would take me to shul [synagogue] with the men. So I had this notion that women are Catholic and men are Jewish!

Once I was under papa’s tallis [prayer shawl] when he had just finished leading a Rosh Hashana [New Year] or Yom Kippur [Day of Atonement] service, and I saw tears in his eyes. I said, ‘Papa, warum weinst du?’ You know? In German, ‘Why are you crying?’

And he said, ‘I just talked with God.’

I asked him, ‘Does it hurt when you talk with God?’

‘No.’

‘So why did you cry?’

‘It’s because I remember such a long time since I really talked with Him.’

Spiritual Awakening: So one Shabbos afternoon, I went with my friends out into the open, and it hit me. I saw why God has to hide, and why it is, also. And I knew at that point. Jews don’t get on their knees, but I got on my knees. You know, despite the fact that we say, ‘V’anachnu kor’eem u’meeshtachvim u’modim’ [‘but we bow and prostrate ourselves in worship and give thanks’]. And I prayed, ‘Please God, don’t let me ever forget this. What I saw right now.’ I was outdoors. It was sort of a picnic round-up. A park. And my friends were on the side and I had just gone a little bit on.... It was almost as if an aura of awareness was starting to come down.

And then I saw why it has to be the way it is, and I was willing and deeply satisfied to allow it to be that way. It made a matrix. There’s always a question of the theophany and how you work out the theology. I like to say that theology is the afterthought of the believer. So the afterthoughts grew, you know? They grew incrementally the more I learned about Chassidus [Hasidic thought], Kabbalah [mysticism], the inner world, the many higher worlds, and so on, so forth. Then that gave it more structure. But the intuition is not what happens in the cortex, you know? [What I understood was] that I’m known, and being seen, and, worthwhile to the Creator. You are a child of the universe. You have a right to be here.

Escaping Austria: My father was first deported to Poland after Kristallnacht [Night of the Broken Glass during the Holocaust]. And he smuggled himself back to Vienna because he didn’t want to go into Poland. He knew Poland was [in] destruction. So he and my brother and I, and several members of the family went because he couldn’t stay there, having been deported. If they would have caught him he would have been in trouble. So we went to Cologne and we paid a thousand marks a person to a smuggler to take us across. We were told where to go and we went and we walked past a German border guard to the place where we were supposed to meet the smuggler...who never showed up. And the sun was about to set. And going back was not advisable. And we davened mincha [afternoon prayer service]. The way I davened mincha that time was very, very much ‘Ayn lanu al mi l’heesh’ayn ele al avinu she’bashamayim’ [‘We have no one to lean on except our Father in heaven’]. And to our relief, after we were finished with mincha, there came a smuggler—not our smuggler but a smuggler who was about to take some Leicas [brand of camera] into Belgium to sell. And he wouldn’t take us unless we gave him the last ten marks we were permitted to take out. So we gave him all the money that we had. He took us across. That was such a moment [of faith].

Spiritual Peeping Tom: I like to say that I’m a spiritual Peeping Tom. I like to see how people get it on with God.

Meeting the Future Lubavitcher Rebbe: We got out of the concentration camp in France—on the Vichy side of it; it wasn’t so bad there. And we were in Marseille, and that’s where I met someone who was a Schneerson—Reb Zalman Schneerson. And I heard him speak and then walked with him to the hotel and asked him to set us up in a little yeshiva [school of Torah learning]. He sent us a guest for Tu B’Shvat [holiday for the trees]. He set us up in yeshiva and sent us a guest and that one turned out to be Reb Menachem Mendel Schneerson (the future Lubavitcher Rebbe). Later meeting his father-in-law, Reb Yosef Yitzhak Schneerson (then the Lubavitcher Rebbe) stands out like, wow! You know? If God would put on a body and be around, it would be like him.

Difficulties in Mental Prayer: At that point I was still very much inside of Judaism. I got to be a teacher at the Lubavitcher yeshiva [a Hasidic sect school] in New Haven. I was trying to go to the library and get something about educational psychology [so] I could be a better teacher. And I saw on the recent acquisition [list] was a book that was called Difficulties in Mental Prayer, by Father Eugene Boylan of Melleray Abbey in Ireland. So I grabbed that book, you know, who knows from difficulties in mental prayer? The rest of the Hasidim [Ultra-Orthodox Jews] don’t know about [it] maybe. The only ones I knew who cared about stuff like that were the Chabad [Hasidic sect] people. So I got into that, and the World Bible, and I found out about Rama Krishna. And so my horizons opened up much more.

Papa, alav hashalom [May he rest in peace], at one point told me, ‘You know that there is somebody—Rabindranath Tagore—an Indian poet,’ but Papa said, ‘Oy! Azeh zu tzaddik [‘he’s a righteous human being’].’ So that there were [righteous] people outside was important.

Howard Thurman: I started to go to Boston University. This is how I met Howard Thurman. I called him my Schvartze Rebbe [Black Rabbi], you know? He was very important to me. He challenged me at one point. I didn’t know whether I should take a class with labs and open myself to someone who is a missionary. You know those goyim [non-Jews], ‘You can’t trust them.’ Right? They all want to convert you.

So I come in and see him and I ask, ‘I want to take a class, but I don’t know if my anchor chains are long enough.’

So he looks at his hand back and forth for five minutes. And finally he says to me, ‘Don’t you trust the Ruach HaKodesh [Holy Spirit]?’

He used those words.

Meeting Thomas Merton: When I went to Cincinnati for my doctorate, I’d go to [Bardstown], across to Kentucky, and then from there get a cab to Gethsemani Abbey and it was wonderful. I had in those days the picture of the last Pope Pius with his eagle nose and severe face. And I figured this guy who wrote the Seven Storey Mountain must be like that. I had written to him that I wanted to meet him. So we met at that desk where I was to meet him. He taps me on the shoulder and I turn around and I see somebody; he could be like a football coach. He had a big grin and smile. And he’d take me up to his place that he calls Shangri-La. That was his hermitage. Later on I met the [Barrigan] brothers there. It was wonderful.

Sufism: They were the Hasidim on the other side of the fence. Stories that would come up like Junayd [Sufi philosopher] having a bunch of disciples who wanted to take the leadership after he’d gone; 20 of them. They want to know why he chose one more than the other. And he said, ‘Bring a bird, a living bird, and I’ll show you.’ All 20 came with a living bird. And he said, ‘Now go to a place where no one can see you and kill the bird, and then come back.’ Nineteen of them came back with dead birds.

And the twentieth comes and says, ‘I couldn’t find a place where no one can see me.’ So you hear a story like this, it touches your heart.

The Desert Fathers: These two guys always come to Father Poemen [of the Desert Fathers]. And they ask him for a verbum [a teaching]; ‘Ah zug a vort’ [‘give us a teaching’], you know? Tell me a word, a verbum, so that they could work on that. One day they came and he said, ‘I haven’t got a verbum for you.’

So they look disappointed and say, ‘How come, every day you give us a verbum, today you don’t?’

He said, ‘Look, they don’t come from me. They come from God. It’s a sign you didn’t do anything with the one I gave you yesterday.’ That’s the kind of stuff that touches me this way. That’s exciting.

Understanding the Trinity: I asked Merton, ‘How do you understand Trinity?’

He said, ‘Well, to me it means, uh, when I say the Creator, [it] is God the Father. When I speak of the redeemer, [it] is God the Son. I speak of the revealer, that’s God the Holy Spirit.’

And oof! Who can argue with that? Taka [really] He reveals, He creates, He’s...you know? I don’t have tayness [complaints] about that. I found a way of accommodating that.

Psychedelics: I had read Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception and I wanted it. Everything that I had done and experienced in Chassidus and davening...it looked to me that there was a corroboration in what Huxley had described. And everything that I had read about [Meister Eckhart] and the people on our side [Jews], Alexander Luria, the Baal Shem Tov [Hasidic philosopher].... In fact, when I later on reported that thing, I yoked it together with the description by the Baal Shem Tov, on his aliyat haneshama [when his soul ascended to heaven], on Rosh Hashanah [Jewish New Year]. So, I was curious about that question.

I met a wonderful person by the name of [Gerald Heard]...do you know that name? He’s another one of those savants that I hold in very high esteem. He was also a friend of Aldous Huxley’s, and his mentor. So I met him and told him that I wanted to do psychedelics, but it was offered to me at a mental hospital in Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan with Hoffer and Osmond. I felt it was doing like big major surgery in a dunghill. I didn’t want to pick up stuff from there.

He said, ‘You are right. I have a friend, he’s at Harvard.’ And he told me about, about Timothy Leary.

Doubt: Faith gets barnacles of superstition. Doubt is what scrapes them off because it always makes sure that you don’t go into beliefs, but you go to faith. Beliefs are a whole bunch of beliefs. And you can make beliefs without number.

Faithing: Faith is not something we have. Faith is a faith-ing, it’s a verb. And unless we have faith-ing, it’s not there. It’s not something I can buy.

Why Am I a Jew?: There were three weeks in which I was having a very deep struggle. Am I a Jew because to God I’m committed, because God wants me to be a Jew? Or am I a Jew and I don’t give a damn what God wants? Because I’m a rabbi, and I make my living that way? So there is all this outer stuff, and the inner is a great struggle.

What’s the Point?: After the Holocaust, you know, all the questions keep coming up about the theodicy. If God is good, how could this be? So these questions are always there. So whenever I get to the door of the doubt, maybe everything is stupid...and I’ve been there also. There are moments of ‘no exit.’ All those things that the existentialists were talking about where everything looks grey, stupid, and the work of an imbecile; the universe. And being there—that’s a hell. That’s not a hell in which you get punished like in purgatory. The hell is, ‘Then what’s the point?’ You know? ‘Then what’s my life for?’ And then suicide makes sense and all that kind of stuff. So if I hadn’t been there, I wouldn’t even know about it to talk. So I’ve been there.

This Too Shall Pass: On the New York subway, you have the straps that you can hang on. What are these straps that you can hang on? I find that’s very much an understanding that gam zeh ya’avor [this too will pass.] I used to have rings like that that I would give to people. When I was in Israel the first time, I went to a Yemenite silversmith and asked him to engrave a ring for me with gam zeh ya’avor because that’s a story with King Solomon. A ring that he could use for all occasions. When he is happy, gam zeh ya’avor. When he is sad, gam zeh ya’avor. That’s on the ground of Buddhism, everything changes. Rav Nachman has it very strong, you know? Nothing is steady. The world is a dreidel [spinning top]. What is above goes below, what is below goes above. So don’t trust that moment, either. Neither the moment of elation nor the moment of depression.

The Sacred Routine: The sacred routine is the life belt because every once in a while you say one of those words in which the light shines in again. If I had all my theophanies all at once, I would be blown out; maybe out of existence. Or, I would be so enlightened that I couldn’t do anything in the world. Right? I would be incapacitated. So there is a forgetfulness that’s also necessary to have. Rav Nachman [founder of the Breslov Hasidic movement] put it so beautifully: Every insight that you have from your soul, you have to teach it to your body. Because the soul, it’ll evaporate. It’ll go away. But the body will remember. And when you need to, you can draw it up from the body again. It’s a beautiful teaching.

Dark Times: Look, this is my fourth marriage. So you can imagine each time you go through a divorce that you have such dark places. You never make such a choice easily. And when it happens, you go into that dark, lonely place and it looks like if there is still a little bit of life there, deep, that says you must continue, this is not the end of it all. But you know what? Then it doesn’t come so much from above as it comes from below. If you want to talk chakras [the body’s energy centers], it comes from the first chakra. Not even from the second chakra, it comes from the first chakra. Or people talk about tachtunig [for below], you know? The Shechina [Divine presence] is below, it’s not above. That’s the whole point of the Shechina. Earth, Malchus [the Holy Kingdom], the Shechina is always below. And underneath are the everlasting arms.

The Feminine: Reb Levi of Berditchev [Hasidic philosopher] was teaching that the letters mustn’t touch each other because otherwise they would displace the white letters of the Torah. And until Moshiach [Messiah] comes, we won’t be able to read them. But when Moshiach comes we’ll be able to read the white letters of the Torah. And my sense is that is what surrounds the black is always the feminine. And this whole business of ordaining women—I wrote that the important Halachic [Jewish law] decisions cannot be made anymore by men alone. You have to have women in that because they bring another awareness to it. And it’s very important also to teach, to bring rabbis, women rabbis, to the place...where they don’t have to emulate the male mind.

Enlightenment: Once, a student asked me about how come when you have a moment, you’re zapped and you’re enlightened, that it doesn’t stay with you? So I said, ‘When you get laid do you stay fucked?’ That’s the way it is. That life continues. If I wouldn’t have the up, I wouldn’t have the down; and we have no down, we wouldn’t have the up.

Greatest Wish: I don’t go anymore for the old fashioned notion of Moshiach [Messiah]. I wrote a piece about rishi [an enlightened person]. You know about that word rishi? In Vedanta [Hindu philosophy], there are seven beings that hold their mind on the world. And I believe that the problems of the world can’t be solved on the level which they occur. The karma that’s coming down the road, if he would oppose it, we would have such a crash it would be terrible. If you have seen people do curling? So you have the sweepers. So you need to have people who can sweep the karma so it won’t crash against each other. Now the Western [religions] and Islam, for instance, could use sweepers. But you can’t sweep on this plane. So the place where the problems originate from is on a much higher vibrational level. Shamans claim that they can go into there, but they’re very idiosyncratic and you can never know whether this is their personal thing or something else. I wanted to bring together a group of people, and I haven’t got the energy anymore to push that because I’m not good at birddogging projects. But what I had hoped for is that we would get like traffic controllers; groups of seven to be in one place, and they’d be in telepathic contact, and hold their mind on the troubled spot of the world. And try and recalibrate things on the subtle plane. This needs an ensemble of work on the shamanic level. And could you imagine if we were to have such a group and they could go and tweak—turn down the Allah’u Akbar [literal translation: “God is great”], and raise up the Rachmim Rachman [referring to the merciful God] in Islam. In Christianity, if they could turn down some of the church fathers and their thing, and turn up a little bit of: ‘Whatsoever you have done unto the least of my brethren....’ In Judaism the same thing. More V’ahavta l’reacha kamocha [love your neighbor as yourself] and less, Yehareg v’al ya’avor [kill or be killed, martyrdom]. All these things are important. I wrote to George Soros and I wrote to Templeton about it and they didn’t respond. They thought it was flaky. But I think that it would pay to put several billions of money into the training that’s necessary in [transversal sociology] to get those minds to mesh and to find the volunteers who would be willing to be trained to be rishi controllers of the planet. So that’s my greatest wish. I have a sense that’s Moshiachdic [Messianic times].

Corporations: The thing that is happening right now—it’s not governments anymore—it’s the international corporations. Global corporations. And they need to be able to have their timescale tweaked to seven generations and away from the quarterly bottom line. This is very special work that needs to be done, and right now there is hardly anybody who understands that this work is necessary. If you ask what’s my greatest wish, is that this should happen; that people should become aware that there is a need.

We Are All Jews By Choice: When people were teaching Judaism in the past, you had no choice. You were born a Jew. You were in the ghetto. If you didn’t behave as the expectations [were], you were out. Today, every Jew is a Jew by choice. Everyone is a Jew by choice. There needs to be a retooling of access for Jews by choice, instead of saying, ‘The law is such, and I don’t want any loopholes,’ because I expect people want to get out of the law. Today we need loopholes to get into the law. I got a beautiful letter from a woman who’s married to an non-Jew, and she’s so, so full of heart and soul, and everything. And, places didn’t accommodate her. And she gave me thanks for Jewish renewal that accommodated her, in a way. Reb Tirzah Firestone was married to a minister before, and at the same time she got her ordination from me. So, you know, there’s a whole other way of talking about to Jews by choice.

Psycho-semitic Souls: Then there is a whole group of people that are what Jean Houston likes to call psycho-semitic souls. It’s a nice pun, but they are. Like someone says, ‘I’m a New Yorker, you know [that I’m] Jewish.’ And there are so many people like that. And halakhah [Jewish law] hasn’t made good room for it. The synagogues haven’t made good room. But these people are a sort of the allies of Judaism; the affiliates of Judaism. And at the time of the temple we would take their sacrifices and make room for them, and they would join in the choir in the temple, and so on. We need to make that echelon legit so that people will know that to whatever extent they want to be affiliated, there’s room for them.

Daniel’s Reflection

Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi was a true gaon [great scholar and teacher] of our generation and I was so very lucky to spend two afternoons with him at his home in Boulder, Colorado to understand the pivotal spiritual experiences of his life.

He was born in 1924 in Poland (now Ukraine), and raised in Vienna until his family was interred in a detention camp in Vichy, France during World War II. His family emigrated to the United States from France in 1941. Reb Zalman was ordained as a rabbi within the Lubavitcher Hasidic sect, and, along with Shlomo Carlebach, was sent as an early emissary of Chabad to campuses. He was kicked out of the Chabad movement when he advocated for the use of LSD to promote spiritual experiences. This break from the rigidness of orthodoxy allowed him to experiment with Jewish and interfaith spirituality to create the Jewish Renewal Movement. Through Jewish Renewal, Reb Zalman created a worldwide following and resurgence in Jewish spirituality that I have personally benefited from and which will impact generations. His friendships with the Dalai Lama, Thomas Merton, and many other spiritual leaders of his time was a breakthrough for a Jewish leader. He was also initiated as a member of the Inayati Sufi order founded by Pir Vilayat.

My first introduction to Reb Zalman happened a few months before the interview. I went to meet him to share Portraits in Faith. I felt sheepish as I shared with him that this project was not my full-time job; that I was actually a marketing director for Procter & Gamble.

He smiled and said, “That’s perfect!”

I said, “Really? Why?”

Reb Zalman’s response: “P&G’s first products were soap and candles, right? Purity and light!”

I felt instantly embraced and included.

In the middle of our interview, Reb Zalman got an emergency call that a son in Israel had been hospitalized. He rushed back from the phone to tell me we had to stop; he needed to go pray. He went to his small office area, pulled the curtain, and I was escorted out by his assistant.

At first the “small me” was disturbed. I’d flown all the way there to interview him. And then, of course, I realized the sanctity of the moment and what I had been shown. We resumed the interview the next afternoon while he awaited news of his son, and he thanked me for the positive distraction which kept him from worrying. Thankfully, his son was released and was OK, but the lesson for me was large.

I have struggled with where Judaism fits into my life now that I have had so many experiences with many walks of faith. Reb Zalman helped me feel still welcome in my Judaism. He showed me all religions are flavors of a much bigger metaphysical reality that cannot be defined. When he described the great spiritual awakening that happened to him as a child (while walking in a park when the heavens opened up to him), he dropped to his knees and said, “God, don’t ever let me forget this moment.”

That story helps me understand my own sense of urgency to hit my knees twice a day to pray, even though this is considered prohibited in Judaism because of its link to idolatry. When I understand Reb Zalman was initiated as a Sufi, it helps me to understand the profound experiences I have had while praying in a mosque for Friday prayers in Dubai, or chanting with Hare Krishnas in Alachua, Florida. And Reb Zalman’s friendship with Thomas Merton from whom he came to understand the Trinity as God the Creator, God the Redeemer, and God the Revealer, gives me permission to understand my deeply powerful but unexpected meeting of Christ in a dream.

I really believe that this expanded holiness and sanctity of all ways to God was the message of Reb Zalman’s life. That the world of God and spirit and holiness is ever expanding and much larger and much more inclusive than we take it to be. He helped us see that our Judaism was not as particularistic as it appears—that all of humanity is part of a holy society. And that we can even participate in each other’s rituals to understand and become closer to God.

Reb Zalman gave me confidence that I was on a sacred path with Portraits in Faith. I honor his memory and I honor every nook and cranny he exposed for us to leverage to get closer to God and each other.

Explore the portraits by theme

- happiness

- grief

- addiction

- sexuality

- sobriety

- transgender

- alcoholism

- suicide

- homelessness

- death

- aggression

- cancer

- health

- discipline

- abortion

- homosexuality

- recovery

- connection

- enlightenment

- indigenous

- depression

- meditation

- therapy

- anger

- forgiveness

- Doubt

- interfaith

- worship

- salvation

- healing

- luminaries