Valarie Kaur

Venice, California, USA

God Is A Way of Being In The World

When I was a child, I loved listening to my mother sing kirtan (the sacred poetry of Sikh tradition). My heart swelled with a love that had no bounds. I remember the shock the first time I opened our translation books of the Guru Granth Sahib [the Sikh canon of wisdom]. The heart of Sikh wisdom is Ik Onkar [‘oneness, ever-unfolding’], but it was translated as ‘One God.’ My translations of sacred Sikh poetry contained Christian words like ‘Lord,’ ‘thy,’ ‘salvation,’ ‘kingdom,’ and ‘sin.’ It was as if my entire faith tradition was given back to me filtered through Christian terms. It didn’t sit well in my body, but I didn’t yet have language for, or understanding of, what I was given.

Many years later, I learned that the first English translations of Sikh scripture were done in the colonial era to butter up our faith in the eyes of the British, to make us palatable, to say, ‘Look, we are monotheistic and believe what you do.’ So much of my life since then has been an attempt to decolonize our tradition, to get back at the essence, to render language that more closely approximates the feeling in my body—the mystical transcendent experience of Oneness I had as a child. My work now is to offer Guru Nanak’s medicine of love for a new time.

I went to a mostly white, conservative Christian public school. I had a series of aggressive confrontations with friends and teachers who tried fervently to convert me to Christianity. They said that there was only one way that I could be saved—to say these magic words: “I accept Christ as my Lord and Savior.” I didn't know about the state of my soul, but I knew that my grandfather surely was not going to be sent to hell. I defended my family.

One woman came to our house and did an exorcism on me. She started to speak in tongues and said that every time I was confused, it was the devil inside me, speaking to me. I was made to question even that transcendent experience of Oneness that I had as a child: Is this mine? Is this a trick? I found myself feeling very...alone, distraught, despairing. I had many nightmares of Judgment Day; my family left behind, all of us going up in the flames.

One Sunday morning, Papa Ji, my mother’s father, took me to the gurdwara [the Sikh house of worship]. I hadn’t been there in so long. I was lost in my books, trying to find the answer to my pain. My grandfather sat with me. Sikh worship consists of listening to the kirtan, immersing in sacred songs of love and letting the music expand you. The kirtan was playing, the voices rising, the harmonium sounding. I looked at my grandfather and his eyes were closed. He was inside of the music. But my mind was racing. I was thinking about my best friend, and my teacher, and the priest standing in front of the congregation to condemn us. I started to get really angry. Furious. As if in a dream, I left the gurdwara. My grandfather’s eyes were still closed. I marched right out and went down the streets of Fresno. I found the nearest church and banged on the door. I was going to confront the priest, in front of the congregation. I was in a fever.

I knocked. An older white woman in a flowery dress opened the door. She said, “My dear, can I help you?” She had a look of confusion on her face. She was the church organist. The pews were empty. Christians finish praying earlier than we do.

I said, “Oh I…. Can I sit and hear you play?”

She said, “Yes, of course, my dear.”

I sat, but I was looking for the exit. Then she placed her fingers on the keys, and it was like a thousand birds lifting from a tree at once. My heart was pounding, swelling, lifted up into the music. I was traveling back in time, or perhaps up into the heavens. I saw an image of Jesus, his arms outstretched, and there were lines from his arms that started to make the Ik Onkar symbol of our faith; the Oneness that always is. Like a beautiful canopy over the whole sky, the whole universe. Tears were streaming down my face.

The woman stopped playing, turned to me and said, “Are you OK?”

I gathered myself together. I’d just had a mystical experience—that transcendent taste I longed for, that I hadn’t had since I was a kid—in a Christian church! I came there to do battle and the church transformed into my sanctuary.

I looked at her and said, “I can’t believe in a God that would send me to hell.”

“Well, I can’t either.” She laughed and added, “There are some people who don’t agree, of course.”

Her name was Fae. I began to sob. She hugged me. She was the first Christian I met who did not think I was going to hell. We sat in that space on the margins. And we talked for a long time.

Fae didn’t have to open that door to let me in. I didn’t have to walk through it. But in that meeting place, there was medicine that she gave me, and it returned me to myself.

We live in such a convulsive, catastrophic era in history. We don’t know if we’re going to make it. I see the future as dark. I ask myself every day, “Is this the darkness of the tomb? Or the darkness of the womb? Will America devolve into a kind of civil war? Or will we birth a multi-racial democracy? Will our species end within a few generations? Or will we birth a sustainable way of being with the earth?”

Some days are so deadly, I can taste ash in my mouth. But when I lift my gaze, I see people who have no obvious reason to love one another come together in unexpected spaces, take each other's hands, weep with each other, grieve with each other, organize with each other, serve each other, love each other. In those moments, I see the finest expression of God, of what we could be when we stand in the truth of our Oneness. I see the world longing to be born.

Daniel’s Reflection

Valarie Kaur is a celebrated and truly revered social justice and interfaith peace leader who has arisen just when our civilization needs her most. She is a Stanford-Harvard-Yale educated lawyer, the author of the best seller, See No Stranger: A Memoir and Manifesto of Revolutionary Love, (One World, Reprint edition, September 7, 2021) and leader of The Revolutionary Love Project (revolutionarylove.org). She is sought out by presidents and religious leaders alike to bring new ideas and new practices to heal our broken society.

Valarie is an American Sikh whose grandparents immigrated from India and became farmers in Clovis, near Fresno, California in 1913. She was propelled into the social justice scene when her family friend, Balbir Singh Sodhi, was killed in anti-Muslim violence after 9/11 because he was a brown person wearing a turban. Her TED Talk, where she lays out her vision for Revolutionary Love as a social justice strategy, has been viewed 3.3 million times.

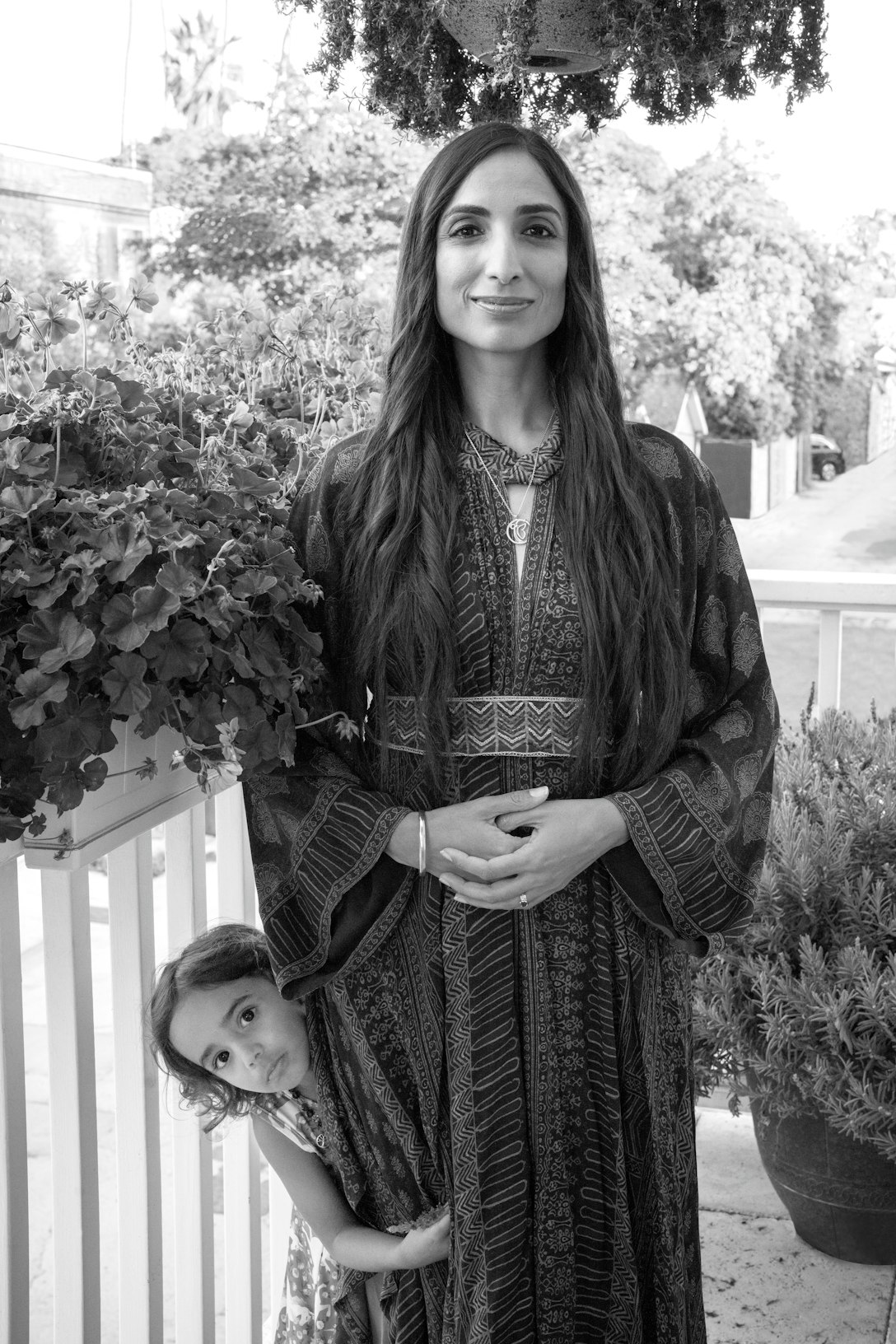

I am so grateful that Valarie Kaur agreed to write the foreword to my book, Portraits in Faith, in 2021, but it would be another three years before I could interview her and make her portrait because of the COVID-19 pandemic. When that day arrived, I made my way to her home in Venice, California where this larger than life figure presented as just another busy mom. Valarie’s husband (a writer-director) was on a business trip, her son was in the midst of tabla drumming lessons, her little girl was reluctant to let go of her mother’s leg, and their dog, Shadi, was running around, overexcited. I noticed a beautiful poster on her wall where the artist Shepard Fairey depicted Valarie for his REFRAME series with Amplifier.

We made a portrait before daylight subsided. Her daughter didn’t want to leave her side. I thought her little girl would distract from the portrait meant to honor this woman I admire so much. But then, as the Universe worked its magic, we created a wonderful image of the two of them that I call “the emerging Divine Feminine” that is so eager and so needed to transform our consciousness today.

After the portrait, we moved to a small deck off the back of her house. Our interview lasted into the evening. Valarie shared that she was moved deeply to be on the receiving end of what I call Sacred Listening.

What moved me was the clarity that Valarie has about the role of the transcendent in her social justice work. This transcendent connection to all of creation and the sense of protection was instilled by her grandfather (Papa Ji) who, when she was a child, would put her to bed at night reciting the Sikh prayer, Tati Vao Na Lagi: “The hot winds cannot touch you.”

That sense of connectedness and groundedness disappeared for many years as Valarie was confronted by the Christian society around her that was spewing the message that only by accepting Christ as her saviour would she and her family be saved.

It was a pivotal faith experience that shook loose those messages. Filled with anger, Valarie went to a nearby church to confront leaders, only to be greeted by a church organist who invited her in and whose playing was like “a thousand birds lifting from a tree at once.” Then Valarie had a vision of Jesus with outstretched arms making the symbol of the Sikh proclamation of Ik Onkar, meaning, ‘oneness ever unfolding.’ Her fighting spirit and wish to confront led instead to a deep, tearful understanding of Oneness. I loved how Valarie put this experience into both a metaphysical, man-to-God understanding as well as a human to human understanding when she said: “You are a part of me I do not yet know.”

Valarie’s stories resonate with me because I grew up in the 1960s and 1970s in Atlanta, Georgia, and lived in a very ethnocentric Jewish family. I attended The Hebrew Academy of Atlanta, complete with my little tzitzis (fringes) and yarmulke (head covering). A switch to public elementary school in fourth grade required me to confront Christian bigotry and bullying. But as I grew older, I had experiences of the beauty of other traditions, especially in the African American church. My family participated in Camping Unlimited, a unique summer camping experience for Jewish and Christian, White and Black kids to come together in peace building activities. Even Dr. Martin Luther King’s kids participated. I felt a deep sense of reverence for those ‘others,’ including the many priests and nuns we met.

I grew up with parents who always had another space at the table for anyone. My own experience of meeting Jesus in a dream makes me smile when I heard about Valarie seeing Jesus make the symbol of Ik Onkar that there is only one God. It reminded me of another Portraits in Faith interview where a Jewish man asks God to reveal himself in a meditation only to be greeted by an image of an elephant-headed deity who winks at him and says, “I am here, where are you? I am here, where are you?”

I believe that is what we do for each other in interfaith work when we work to see others as a part of ourselves that we don’t yet know. My interview with Valarie ended with the powerful thought that God is “a way of being in the world.” I believe this with all my heart.

This will sound sacrilegious and offensive to many people, but I don’t believe it matters if there is a God or not. I believe that I am a better person and am contributing to the consciousness of society better and deeper when I live as if there is a great Sacred Presence. And I believe I help create that which is Godly by not creating harm, by honoring my commitments, by being of service to others, and by enjoying life. And I hope to continue being this way in the world as much as possible. Being with Valarie Kaur reminds me to create sacredness in all of my interactions and in all of my life.

Thank you to Valarie Kaur for her scholarship, for her writing, for her loving kindness, for her instruction and role modeling, and her way of being in the world.

Explore the portraits by theme

- happiness

- grief

- addiction

- sexuality

- sobriety

- transgender

- alcoholism

- suicide

- homelessness

- death

- aggression

- cancer

- health

- discipline

- abortion

- homosexuality

- recovery

- connection

- enlightenment

- indigenous

- depression

- meditation

- therapy

- anger

- forgiveness

- Doubt

- interfaith

- worship

- salvation

- healing

- luminaries