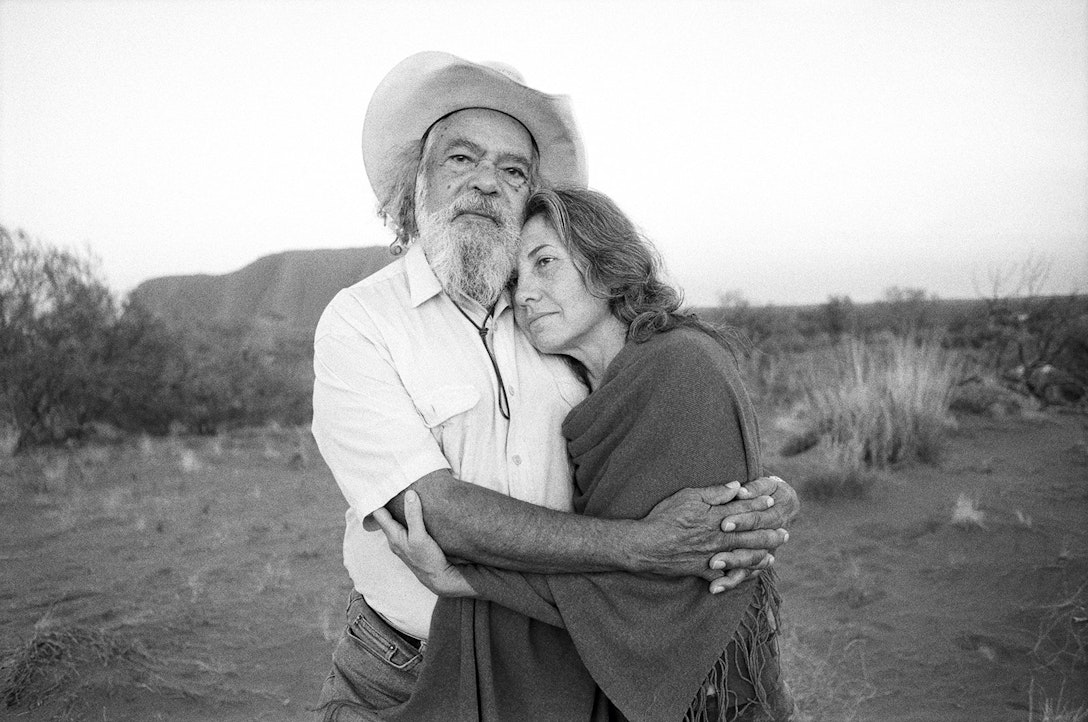

Bob Randall

Mutitjulu, Northern Territory, Australia

THE MOTHER WOULD HOLD YOU

The policy of the government was to take any half-caste kids they saw. So when they were arresting my family for killing and eating cattle, they said, ‘Oh it’s the half-caste boy there,’ and they grabbed me at the same time. And then they put my family in chains. We walked from Angas Downs Station to Alice Springs, nearly 200 miles. That’s 500 kilometers today by car. So beyond the [policeman’s] camel was my family and I was the little boy. My auntie and my mother shared carrying me on their hips, but they had the chains; they were all linked up with chains. And they handed me, the half-caste boy, over to the institution in Alice Springs. There were hundreds of little children like myself. I was forced to wear clothes straight away. I never wore clothes [before] in my life!

When I was beaten, I felt really alone because the other kids were terrified to go near me or help me. They too were afraid of being beaten. We had to connect with the Sun or Earth as quick as we could, so that they could have a chance to comfort us. And sometimes we’d just lie on Earth and just say, ‘Oh, I’ve had it. I need you to hold me.’ You know? And then she would; the mother would hold you. And sometimes we’d just say to the Sun, ‘I need you to hold me, mom.’ And she’d hold us. We only had those two mothers. Our [real] mothers were taken away from us. They weren’t there. The people who said they were our mothers, the men who were our fathers, wouldn’t even touch us because of our darkness. But the two mothers, the Sun and the Earth, they never, ever rejected us, ever. So even though I lost my physical ‘rellies’ I learned to trust and believe in the other greater relatives.

Through that connecting, I’d say ‘faith’ would be a good word for it because it is dependent through something you don’t understand, but know it works. Because it’s not tangible, but it’s so clear in yourself, you know it's real.

[As an adult, while flying on an airplane] I was looking down and all of a sudden there was an empty chair right in front of me, and it felt as though someone was there. I looked, there was no one there, but then I heard, ‘I have that song for you.’ This voice, there it was. ‘Get your pen and paper.’ And I leaned back and I opened my briefcase, got pen and paper and, and I just wrote that song that I felt was being given to me at that moment. It was the first time I was reminded of the way I was taken.

I sang it when I got home that night. And the effect it had on everybody there was just beyond anything I imagined. I started to feel OK that I was dealing with this experience, which I think must have been bottled inside me. And now was the time to release it—when I sang the song. And other people were releasing their tears when they heard me singing the song. I always acknowledged that my mother came to me and gave me this song, because it’s from a mother telling me the story about the loss of [her] children. That’s why I wrote it, ‘Brown skin baby, they take him away.’ It’s exactly the same lyrics I got at that first time. I sing it today the same way.

Daniel’s Reflection

Uncle Bob was considered one of the most important Aboriginal elders in Australia because of his activism in exposing the “stolen generation.” The “stolen generation” was named for the practice of the Australian government to take mixed-race babies from their mothers to be raised “white” in missionary schools, thousands of miles from their homes. Bob was inspired by an inner voice he understood to have been his mother’s to write the song, “Brown Skin Baby (They Took Me Away),” which became a rallying cry in Australia to end this horrific practice.

I met Uncle Bob Randall and his wife Barbara at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in 2009 in Melbourne, Australia through my producer, Clare McGrath. And in one of the most special experiences of my life, Clare and I were invited to spend three days with Uncle Bob and Barbara in their home in the Aboriginal community, Mutitjulu, next to the monolith Uluru, in the Northwest Territory. I had never seen such clear, star-filled skies, nor been so scared by the howling of the dingos at night. I deliberately chose to sleep outside. Over those three days, I got to know Bob and Barbara and learn about the devastation of the Aboriginal peoples and culture that has been happening for generations now in Australia. What makes it so sad is that the same exact thing has been done around the world by western white settlers in every continent against indigenous peoples, including the practice of taking mixed-race babies away from their mothers to raise them “white.”

The most special gift I received being with Uncle Bob was a deepened understanding of God in all of creation. And by all of creation, I especially mean Mother Sun and Mother Earth (Aboriginals consider the moon to be male: Father Moon). Bob spoke of being beaten in the missionary schools. All the children had to comfort themselves were Mother Sun and Mother Earth...and she would hold them.

Bob also conveyed the great interdependency that humans have with animals to the point of his being willing to give himself to the crocodile if the crocodile chose him for a meal. When Bob and Barbara came to Cincinnati for a visit, we held a gathering with them in my home where Bob offered this blessing before the meal: “We thank the fish people for giving of themselves and we thank the plant people for giving of themselves.”

Another great example that Barbara likes to share is a story from when she and Bob were driving on a desolated Australian highway. Barabara said that she had never seen an emu and would love to see one. So Bob said, “Oh you’d like to see an emu?” and he called for an emu. Within a few miles, in the middle of the highway an emu was standing right on the center line of the road.

Bob also described relatives who were related to the weather and could change it. And, of course, trees and stones were his family as much as was the person standing next to him.

Uncle Bob suffered from heart problems and died on May 12, 2015. His memory is strong with me and I am actively in touch with Barbara who has become a friend. Receiving the wisdom of indigenous peoples is one of the great gifts of this project.

Note: It is an Aboriginal custom to not view images of those who are deceased, but Uncle Bob gave permission for his image, voice, and words to be used after his death.

Explore the portraits by theme

- happiness

- grief

- faith

- addiction

- sexuality

- sobriety

- transgender

- alcoholism

- suicide

- homelessness

- death

- aggression

- cancer

- health

- discipline

- abortion

- homosexuality

- recovery

- connection

- enlightenment

- indigenous

- depression

- meditation

- therapy

- anger

- forgiveness

- luminaries

- interfaith

- worship

- salvation

- healing